How many people are given the death penalty in India? How many executions happen in India?

In India, capital punishment is awarded for murder, gang robbery with murder, abetting the suicide of a child or insane person, waging war against the government, and abetting mutiny by a member of the armed forces. It is also given under some anti-terror laws for those convicted for terrorist activities. The death sentence is imposed only when the court comes to the conclusion that life imprisonment is inadequate based on the facts and circumstances of the case.

The Law Commission of India released a report in 2015 recommending that the country move toward abolishing the death penalty, except in terrorism cases to safeguard national security.

Currently judges in India can impose the death penalty in the “rarest of rare” cases, including treason, mutiny, murder, abetment of suicide, and kidnapping for ransom. In 2013, an amendment to the law permitted death as a punishment in cases where rape was fatal or left the victim in a persistent vegetative state, as well as for certain repeat offenders.

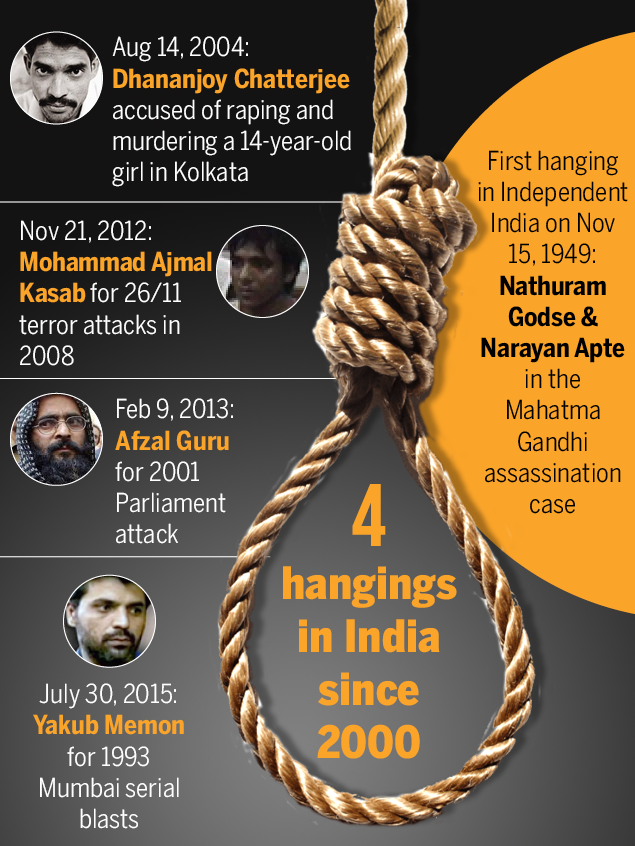

According to the Law Commission report, executions in the recent past have been few, with significant time gaps. Only three convicts were executed over a period of 10 years, one each in West Bengal (2004), Maharashtra (2012), and Delhi (2013).

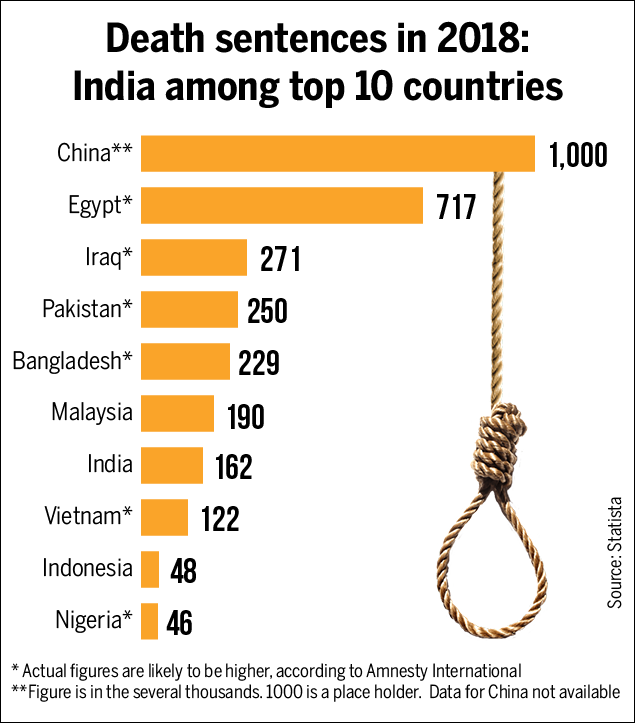

India saw an execution-free period of seven years between 2004 and 2012. The latest was the execution of Yakub Memon. The Court found him guilty of being behind a series of explosions in Mumbai in 1993, killing more than 250 people. On average, the courts sentence 129 people to death row in India every year, according to the National Crime Records Bureau.

Data shows a huge gap between death sentences pronounced and actual executions. According to an ACHR report and National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) data, there have been several death sentences between 2001 and 2011. But the authorities actually carried out only a few of these. Despite the fact that death sentences rarely convert to executions in India, the Law Commission recommends abolishing the penalty in most cases.

According to leading criminal lawyers in india, people sentenced to death by Indian courts face long delays in trials and appeals. “During this time, the prisoner on death row suffers from extreme agony, anxiety, and fear arising out of an imminent yet uncertain execution,” the Law Commission said. It added that solitary confinement and harsh conditions imposed on prisoners were degrading and oppressive.

The Law Commission report cited the following reasons while advocating the abolition of capital punishment:

- Developments in India. India has made significant progress since the last report in 1967. The level of education, general well-being, and socio-economic developments are vastly different today.

- Death penalty as a deterrent is a myth. The decline in murder rate in India has coincided with a decline in rate of executions. This raises questions about whether the death penalty has any greater deterrent effect than life imprisonment.

- Arbitrary sentencing of capital punishment. The Supreme Court has expressed concerns over arbitrary imposition of capital punishment. In most cases, the courts have affirmed or refused to affirm the death penalty without laying down legal principles.

- Long delays leading to extreme agony. Death row prisoners continue to face long delays in trials, appeals, and executive clemency. During this time, prisoners on death row suffer from agony, anxiety, and fear because of an imminent yet uncertain execution.

- International developments. India has retained capital punishment while 140 countries have abolished it in law or in practice. That leaves India in a club with the USA, Iran, China, and Saudi Arabia as a country which retains it.

The commission concluded that the death penalty does not serve the goal of deterrence any more than life imprisonment.